Searching for Rights in the Shadows Sam and Rajitha’s Haunting Testament to Lost Innocence

A haunting meditation on institutional failure and human resilience

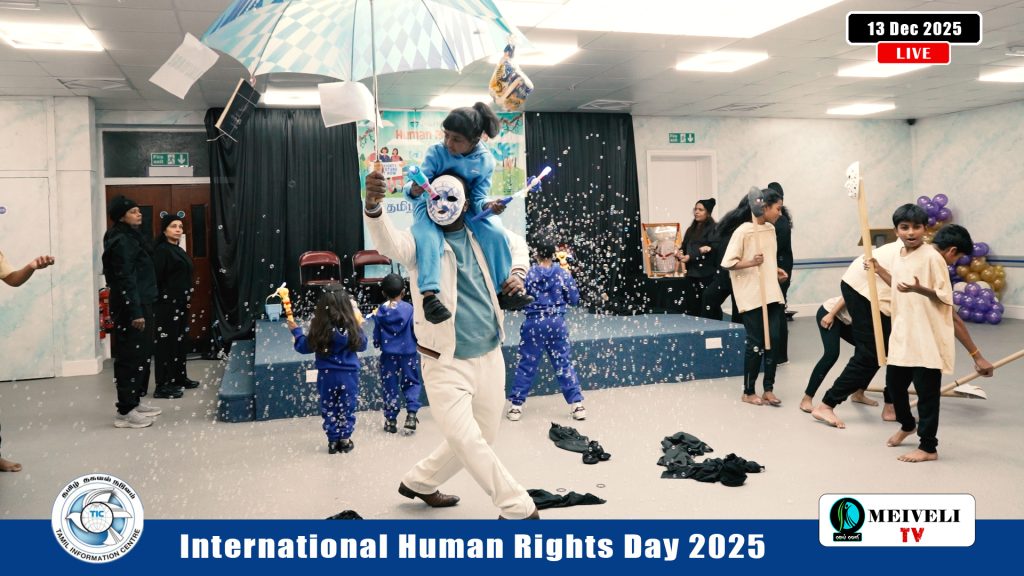

A Review of Meiveli Production “Unreachable Light” Drama

Venue: Punjabi Centre – Ilford

Directors: Sam and Rajitha

Performed by: Meiveli – British Tamil Theatre

In an era where political theatre often stumbles between didacticism and obfuscation, Sam and Rajitha’s latest production with their Meiveli ensemble achieves something far more elusive: it transforms the abstract language of international law into visceral, embodied agony. This is not theatre that preaches; it is theatre that wounds, heals, and ultimately refuses to look away from the abyss of institutional failure.

The Visionary Direction: A Couple’s Unified Artistic Voice

Sam and Rajitha have long been recognized as custodians of Tamil cultural expression within the British diaspora, and this production consolidates their reputation as serious theatrical practitioners who understand that form must serve the fury of content. Their collaborative direction demonstrates a rare synergy—Sam’s authoritative vocal presence and Rajitha’s keening lament create a call-and-response structure that echoes ancient Tamil poetic traditions while speaking directly to contemporary humanitarian crises.

What distinguishes their work is the refusal of easy catharsis. Where lesser directors might offer redemptive closure, they leave us suspended in the liminal space between hope and despair—precisely where displaced communities exist in perpetuity.

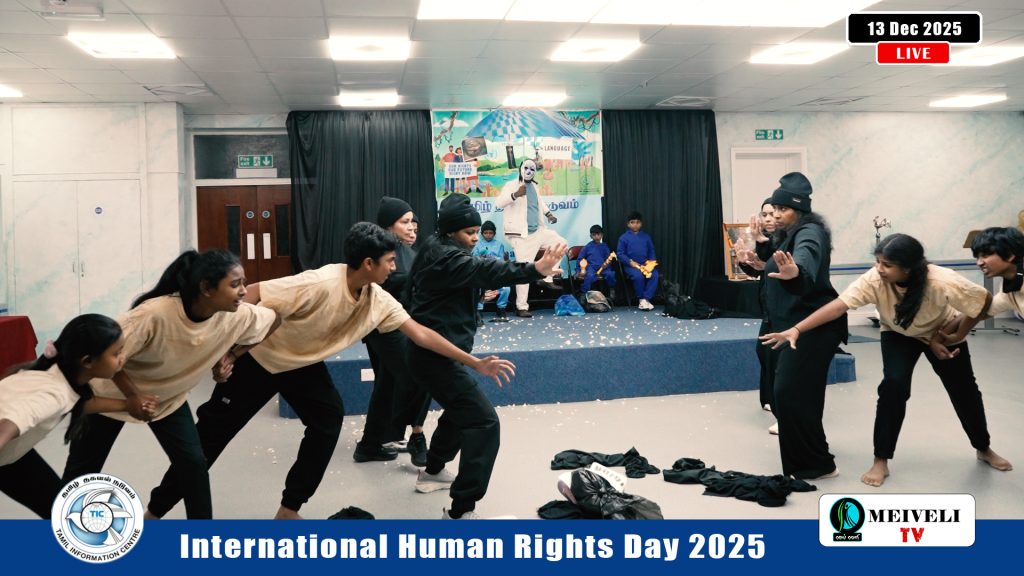

Radical Staging: Collapsing the Distance Between Witness and Witnessed

The decision to abandon the proscenium arch in favour of performing on the audience floor is not mere gimmickry but a profound ethical choice. By literalizing the collapse of distance between spectator and sufferer, Sam and Rajitha implicate the audience in the failures they depict. We cannot retreat into the comfortable darkness of our seats; the children search among us, their expressions illuminating our faces as much as the performance space. This is theatre as confrontation, as unavoidable encounter.

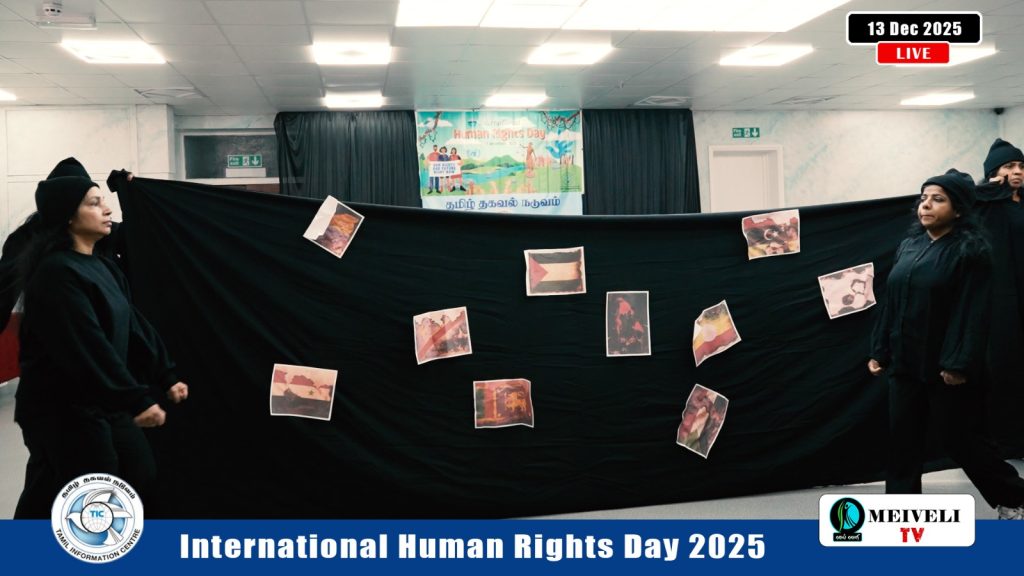

The minimalist staging—black cloth manipulated by women in the background to create shifting landscapes—recalls both traditional shadow puppetry and the aesthetic economy of Brechtian epic theatre. These mothers become both chorus and scenography, their presence a reminder that it is always the older generation who bear witness while the young bear the consequences. The simplicity is deceptive; each gesture, each repositioning of cloth, carries metaphorical weight.

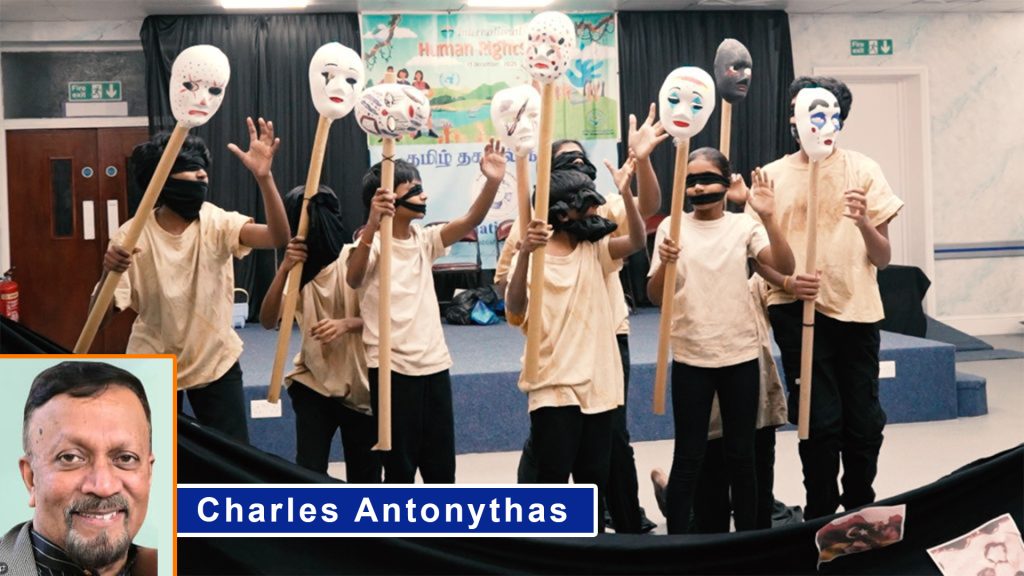

The Children: Innocence as Indictment

To deploy child performers in a work addressing genocide, displacement, and institutional betrayal is a calculated risk that could easily tip into exploitation or sentimentality. That it does neither is testament to both the children’s disciplined performances and the directors’ ethical rigour.

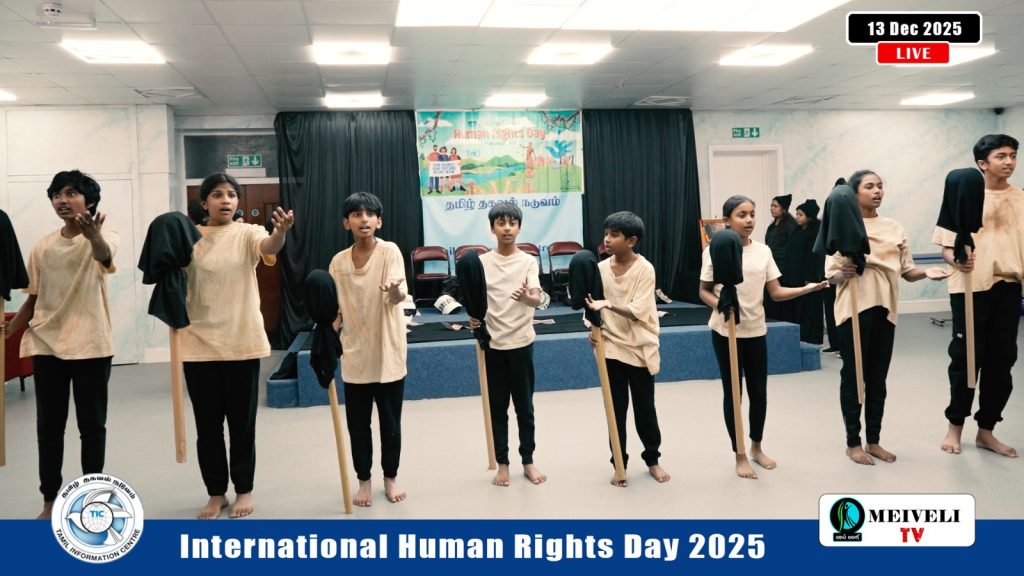

These young actors—students of Sam and Rajitha’s alternative Stage Coach Drama School—deliver performances of startling precision. Their zombie-like movements, the torch-lit searching, the repeated pleadings (“Have you seen it?”) accumulate a ritualistic power. They are not asked to represent children; they are children, and this ontological fact transforms every moment into documentary testimony as much as theatrical representation.

When they mimic the UN’s bureaucratic platitudes, when they are repeatedly shot down by repressive forces, when they emerge from symbolic graves limping back to life—these are not performances that can be separated from the bodies performing them. Any Tamil parent in the audience, as the program notes wryly observe, might indeed find this “injurious to health, especially soft-hearted.” But this is precisely the point: art that does not risk breaking the heart is not art adequate to the enormity of its subject.

The Central Metaphor: Rights as Phantoms

The dramaturgical core of the piece—the litany of rights offered and immediately rescinded—builds with devastating cumulative force. Food, education, language, religion, clothing, livelihood: each is presented with fanfare and snatched away by “dark forces” before it can be grasped. The choreography of this sequence is masterful; the children’s reaching hands are always a beat behind the vanishing objects, like Tantalus eternally denied satisfaction.

But the true innovation lies in the representation of the United Nations. Sam’s embodiment of this institution—masked, emotionally absent yet physically dominating the stage—is a stroke of genius. The umbrella festooned with rights becomes both shelter and shield, offering protection but never extending beyond the UN’s own circumference. His body language conveys monumental indifference, a presence “larger than the UN” itself, which is to say, larger than any actual capacity to intervene meaningfully in human suffering.

The Dialogue of Futility: “We Want Evidence”

The verbal architecture of the play reaches its apex in the extended exchange between Rajitha’s maternal voice and Sam’s UN bureaucrat. The incantatory repetition of “We know that too, but we want evidence” transforms from an administrative requirement to a cosmic joke to an existential horror. Each iteration strips away another layer of hope until we arrive at the absurdist truth: the victims are asked to provide evidence that their victimizers have systematically destroyed.

This is not simply a critique of the UN; it is an interrogation of the entire apparatus of international human rights law, which promises universality while requiring documentation that presumes state infrastructure, which guarantees protection while deferring to national sovereignty, which proclaims inalienable rights while offering only alienation to those who need them most.

The sequence where the children mime cultural genocide, economic destruction, and Western arms proliferation while the UN maintains its mantra of evidentiary requirement is unbearable in the best sense—theatre that refuses to be borne lightly, that insists on its own intolerable weight.

Sonic Landscape: Music as Emotional Architecture

Sam’s dramatic orchestration—the musical score that “dominates the emotions, desperation, authority and inevitability”—deserves particular commendation. In a production that could easily have drowned in its own gravitas, the music provides both propulsion and punctuation. The “war, war, war” sequence, driven by orchestral intensity, creates a soundscape of inescapable violence that needs no visual representation to convey its horror.

Conversely, Rajitha’s final sung prose—”I am trying to reach for you / Are you a distant moon that shines behind the closed sky”—offers not resolution but a fragile, aching beauty. This is not the language of political protest but of metaphysical longing, and its placement after the brutal realism of the preceding scenes creates a tonal shift that is both jarring and necessary. It reminds us that behind every statistic of displacement stands a person still capable of dreaming, still reaching for impossible moons.

The Political Unconscious: Tamil Specificity and Universal Resonance

While the production studiously avoids naming specific conflicts, its roots in Tamil experience are unmistakable—the references to cultural genocide, the super-national destruction of livelihood, the abandonment in “streets of nowhere” all speak to the post-2009 Sri Lankan context. Yet Sam and Rajitha have crafted something that transcends the specificity of a documentary. This could be Palestine, Syria, Myanmar, Yemen, or any of the dozens of sites where international guarantees dissolve before geopolitical expedience.

This universalizing gesture is not an evasion but an act of solidarity. By refusing to delimit their critique to a single conflict, they indict the entire system that produces such conflicts with numbing regularity. The Tamil experience becomes not exceptional but exemplary—a particularly clear instance of a general condition.

Theatrical Lineage and Innovation

The production places itself within a distinguished lineage of political theatre while forging its own path. One traces echoes of Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, with its emphasis on spectator activation and spatial politics. There are resonances with Ariane Mnouchkine’s epic staging and intercultural synthesis. The use of children recalls Bertolt Brecht’s “The Mother,” though without Brecht’s confidence in dialectical resolution.

Yet this is no derivative work. Sam and Rajitha have synthesized these influences with traditional Tamil performance vocabularies—the storytelling traditions of therukoothu (street theatre), the mythic resonances of kaddaikkoothu (கட்டைக்கூத்து) to create something distinctly their own. The mothers manipulating the black cloth, for instance, evoke both Greek tragedy’s messenger figures and Tamil folk theatre’s narrator-demonstrators.

Minor Reservations and the Question of Closure

If the production has a weakness, it lies in its final moments. Rajitha’s lament, while beautifully rendered, risks aestheticizing the preceding brutality. After the hammer-blows of the UN sequence, the shift to metaphorical language—distant moons, mirages, horizons—might be read as a retreat into the consolations of art. There is a danger that the audience, having been refused easy catharsis throughout, finds it smuggled in through the back door of poetic beauty.

However, this may be less a flaw than an acknowledgment of theatre’s limits. Perhaps Sam and Rajitha recognize that no ending can be adequate to their subject, that any conclusion would falsify the ongoing nature of displacement and dispossession. The shift to poetry, then, becomes not escape but the only honest response when political language has exhausted itself—a recognition that some experiences can only be approached asymptotically, through metaphor and music.

The Pedagogical Imperative: Drama School as Resistance

One cannot review this production without noting its pedagogical context. That Sam and Rajitha run an “alternative Stage Coach Drama School” for Tamil children is not incidental to the work’s power but constitutive of it. In teaching diaspora children to embody their community’s trauma through rigorous theatrical training, they are engaged in what might be called “prophylactic witnessing”—ensuring that these histories are not only remembered but metabolized, incorporated into living bodies that will carry them forward.

The children’s “impressive” performances are impressive not despite their youth but because of it. They represent a generation born into exile, for whom displacement is not historical trauma but lived reality. When they ask, “Have you seen it? We have never had them,” they are not merely reciting lines; they are articulating their own condition. The drama school becomes a site where historical memory and embodied present converge, where pedagogy and politics are inseparable.

Meiveli as Cultural Institution

This production confirms Meiveli’s status as more than a theatre company—it is a cultural institution, a repository of Tamil identity in the British context, what the program aptly calls “the source of Tamil art, culture and customs” for the UK diaspora. Sam and Rajitha’s work across multiple domains—education, performance, community organizing—creates an ecosystem within which Tamil cultural expression can flourish even in conditions of displacement.

Their “trade mark” Meiveli encapsulates their artistic philosophy: theatre as shield, as a survival mechanism, as a way of protecting cultural identity from the erosions of exile. This production exemplifies that philosophy, using the disciplined bodies of children to insist on the persistence of memory, the refusal of erasure.

Conclusion: Theatre as Necessary Witness

Sam and Rajitha’s “Unreachable Light” human rights drama is that rare thing: political theatre that achieves genuine aesthetic power without sacrificing its ethical commitments. It neither preaches nor despairs; instead, it witnesses—bears testimony to what has been lost and what continues to be denied.

In an age of humanitarian catastrophes so ubiquitous they risk becoming wallpaper, this production performs the invaluable service of making us feel the abstraction of “human rights violations.” By localizing the general in the specific bodies of Tamil children, by spatializing the collapse of international protections, and by refusing the comfort of resolution, Sam and Rajitha create an experience that lingers long after the torches are extinguished and the UN umbrella folded away.

This is a theatre that understands its task: not to solve political problems (that is for politics) but to create the affective and cognitive conditions under which such problems become indismissible, where the suffering of distant others ceases to be distant, where the audience cannot return unchanged to their comfortable assumptions about rights, justice, and international order.

For the Tamil diaspora, this production offers recognition, catharsis, and the dignity of serious artistic engagement with their community’s wounds. For broader audiences, it offers education, implication, and the uncomfortable gift of having one’s complacency disturbed.

Sam and Rajitha’s children search among us with their torches, asking if we have seen their it (rights). The honest answer is: yes, we have seen them—on paper, in charters, in UN resolutions. But seeing is not the same as securing, and documents are not the same as reality. This production forces us to acknowledge that distinction, and in doing so, performs the irreplaceable work of serious political art.

Rating: ★★★★★

A haunting meditation on institutional failure and human resilience, performed with disciplined passion by the next generation of Tamil theatrical practitioners.